by Mark H. Dunkelman

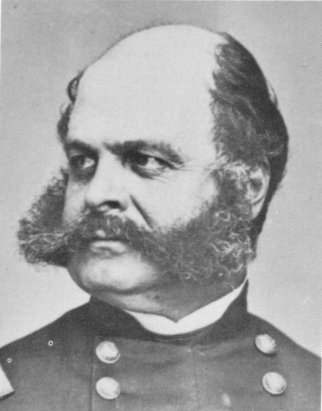

Ambrose Everett Burnside

There was never any doubt about who was Rhode Island’s major hero of the Civil War. But oddly enough, he wasn’t a native Rhode Islander. Ambrose Everett Burnside was born in Indiana, the son of a former slave-holder from South Carolina. After graduating from West Point, Burnside served in the army during the Mexican War. When that conflict ended, he did a short tour of duty at Fort Adams in Newport — his introduction to Rhode Island. Three years of service in New Mexico were followed by a return to Newport, marriage to a Providence woman named Mary Bishop, and his resignation from the army. From 1853 to 1858 Burnside manufactured in Bristol a breech-loading rifle of his invention. But the business failed and Burnside left Rhode Island to take a position with the Illinois Central Railroad under his friend George B. McClellan.

Two days after the firing on Fort Sumter, Rhode Island Governor William Sprague telegraphed Burnside, asking him to lead the 1st Rhode Island Infantry to the war. Rapid promotions resulted from Burnside’s meritorious service at Bull Run and his successful expedition to North Carolina. But as his commands grew, Burnside’s abilities appeared to wane. His handling of the left wing at the Battle of Antietam was roundly criticized. Then followed his brief career as commander of the Army of the Potomac, made infamous by the terrible tragedy of Fredericksburg and the farce called the Mud March. His service during the remainder of the war was marked by further ineptness at Knoxville and during the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg. But his lackluster performance as a military man was countered by his bravery, honesty, and fame. When he returned to his adopted state of Rhode Island, its citizens rewarded him with terms as governor and United States senator, and first rank of its heroes of the Civil War. Burnside was serving as senator when he died in Bristol in 1881. He is buried in Swan Point Cemetery in Providence.

Of course, Rhode Island honored other of her soldiers and sailors during the years after the war for their services in suppressing the rebellion. But time would bring greater fame to Burnside, while obscuring the deeds of other of the state’s veterans. Today, most Rhode Islanders are at least familiar with the large equestrian statue of Burnside in Kennedy Plaza in downtown Providence. Vestiges of the six native Rhode Islanders who served the Union as general officers (full, not brevet rank) are harder to find, and it’s doubtful if the average citizen of our state could name even one of them. The six Rhode Island Civil War generals deserve a better fate than the obscurity that shadows their accomplishments. Let’s get reacquainted with these once prominent Rhode Islanders.

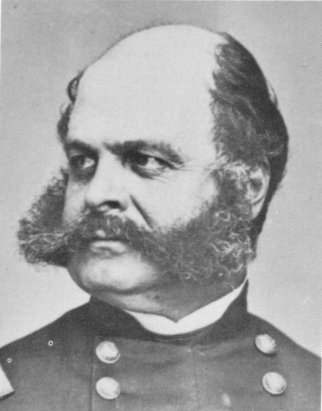

Richard Arnold

Richard Arnold, son of Rhode Island governor and United States congressman Lemuel Arnold, was born in Providence in 1828. His was an old Rhode Island family, and included the infamous Benedict Arnold. An 1850 graduate of West Point, Richard Arnold initially saw service as an artilleryman in Florida, Maine, and California. Then he was selected by General John Wool as a staff officer. For six or seven years he was the general’s aide-de-camp and was involved in Indian affairs in Oregon and Washington. When the Civil War began, Arnold became captain of Battery D, 2nd United States Artillery.

As the Union army’s fortunes began to wane at the First Battle of Bull Run on the afternoon of July 21, 1861, General Irwin McDowell and his staff made an effort to rally troops on the high ground near the Matthews house. His assistant adjutant general, Captain James Fry, later wrote, “There, I went to Arnold’s battery as it came by, and advised that he unlimber and make a stand as a rallying point, which he did, saying he was in fair condition and ready to fight as long as there was any fighting to be done. But all efforts failed.” Arnold joined regular units of infantry and cavalry in an attempt to cover the rear of the routed Union army, and in the process his battery lost all of its guns.

Despite his disaster at Bull Run, Arnold was in command of the artillery of General William B. Franklin’s division at the beginning of the Peninsula fighting. Soon after, Franklin took command of the newly organized 6th Corps, and appointed Arnold his acting inspector general. As such, he was brevetted major for services rendered at the Battle of Savage’s Station. Then a bout with typhoid fever led him to a three months sick leave.

In late 1862, after his recovery, Arnold traveled to Louisiana and a new position as brigadier general and chief of artillery of the Department of the Gulf. As such he participated in the Port Hudson and Red River campaigns, and in the shakeup following General Nathaniel P. Banks’s failure in the latter campaign, he was put in command of the cavalry. During the operations against Mobile, General Arnold was chief of artillery, and his 25 guns and 16 mortars were instrumental in forcing the surrender of Fort Morgan in August 1864. After that campaign, the general obtained a leave of absence. Then, in November 1864, the war at the front ended for Richard Arnold. He was assigned to a retirement board for disabled officers in Wilmington, Delaware, and there he sat out the remainder of hostilities.

At the end of the war he was brevetted to the rank of Major general in both the regular and volunteer service, but his regular rank was captain of the 5th United States Artillery. In 1866 he was assigned to the command of a battery stationed in Little Rock, Arkansas. The remainder of his life was spent on a succession of posts. In 1875 he was promoted major, and in 1882 he rose to lieutenant colonel. Five days after that promotion, while doing duty as acting inspector general of the Department of the East, General Arnold died at Governor’s Island, New York. He is buried in Swan Point Cemetery in Providence.

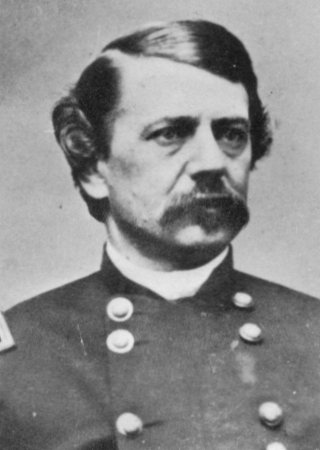

Silas Casey

Like Richard Arnold, Silas Casey came from an honorable old Rhode Island family. Born in East Greenwich in 1807, Casey also attended West Point, Class of 1826, and upon graduation was assigned to the Arkansas Territory. In succeeding years Casey was engaged in campaigns against the Indians — the Pawnees in Arkansas, the Creeks in Alabama, and the Seminoles in Florida, where he attracted attention and received promotions to first lieutenant and captain. His service in the Mexican War as a captain in the 2nd Infantry won him brevets to major and lieutenant colonel for gallant conduct at the Battle of Chapultepec. His Mexican War service also won him the thanks of the Rhode Island General Assembly and a silver vase, the gift of his home town of East Greenwich. In the celebrated storming of Chapultepec, Casey led a picked detachment of 250 men into heavy firing and received a severe wound in the abdomen. At the close of the war, a five months’ voyage via Cape Horn brought Casey to California. In the decade preceding the Civil War, most of Casey’s posts were in the Pacific Northwest, and in 1855 he was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the 9th Infantry.

In 1861, Casey journeyed to Washington and was appointed brigadier general of volunteers. He proved to be a great help in organizing and drilling the raw recruits in the great, new Army of the Potomac, and when General McClellan began his campaign on the Virginia Peninsula, Casey led the 2nd Division of the 4th Army Corps. The campaign appeared to be progressing well — if slowly — until May 31, 1862. On that day occurred the Battle of Seven Pines, or Fair Oaks. That pivotal engagement marked the beginning of the retreat of the Union army, the advent of Robert E. Lee as a Confederate commander, and an end to the military fortunes of Silas Casey.

Casey’s division was posted in an advanced position on the Williamsburg Stage Road, only five or six miles from Jefferson Davis and the Confederate capitol in Richmond. Casey’s men were behind rifle pits, and also occupied a pentagonal redoubt — known to history as “Casey’s Redoubt.” That afternoon Confederate General Joseph Johnston began a great counteroffensive when he attacked Casey’s division in overwhelming numbers. Daniel Harvey Hill’s Division assaulted Casey’s position. Casey was not unprepared, having received reports of Hill’s movements. in the minutes before the attack came, he reinforced his picket line, called in his working parties, harnessed his batteries and formed his troops. Although retreat was inevitable, Casey’s defense was good — so good that Johnston would later recall the number of troops and length of time it took to dislodge the Yankees, and attributed it to their commander. “The resistance was very obstinate,” Johnston wrote, “for the Federals, commanded by an officer of skill and tried courage, fought as soldiers generally do under good leaders; and time and vigorous efforts of superior numbers were required to drive them from their ground.”

Casey’s division lost more than 1,400 men at Seven Pines. In his official report, the general noted that eight of his thirteen regiments were raw troops, and all had suffered from bad weather and poor supplies. “Notwithstanding all these drawbacks, and the fact that there were not five thousand men in line of battle, they withstood for three hours the attack of an overwhelming force of the enemy,” Casey wrote. “It is true that the division, after being nearly surrounded by the enemy and losing one-third of the number actually engaged, retreated to the second line. They would have all been prisoners of war had they delayed their retreat a few minutes longer.” But while Casey was brevetted brigadier general in the regular army, and commissioned major general of volunteers dating from May 31, 1862 — the day of Seven Pines — he suffered in the acrimonious debate which followed the Army of the Potomac’s misfortunes. He no longer saw an active command.

The general stayed in the army, however, and found other ways to serve. His book on infantry tactics was chosen for use in the army in 1862. In the outskirts of Washington, he greeted and trained thousands of just-sworn soldiers from home fronts all over the North, receiving, organizing, instructing, and forming the new regiments into provisional brigades and divisions. For this valuable service, an officer noted, Casey was “exactly fitted.” He presided over the board that examined potential officers for black regiments. He also served on the court martial of Fitz John Porter. (It’s hard to imagine Casey as an impartial juror, because a few months before, Porter had refused to accept him as a subordinate.)

At the end of the war, General Casey was mustered out of the volunteer service and returned to his permanent rank of colonel of the 4th Infantry. in 1868 he applied for retirement, after 46 consecutive years of service. General Casey lived in Brooklyn until his death in 1882, but he is buried on the Casey Farm in North Kingstown, Rhode Island.

George Sears Greene

The descendants of John Greene, compatriot of Roger Williams, served Rhode Island and the nation as legislators and jurors of note and included the renowned Revolutionary War general Nathanael Greene. The next great military man in the family appeared in the seventh generation of Rhode Island Greenes when George Sears Greene was born in Apponaug in 1801. After schooling in Warwick and Providence, George wanted to attend Brown University, but he couldn’t afford the tuition. Instead, he took a job in New York City. Then he received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. He was eighteen years old when he set out in a small sailboat up the Hudson to the Point and a post in the army.

Seventy-nine cadets entered the academy and after the four year course, George graduated second in the Class of 1823. Thirteen years of garrison duty followed, including a stint as mathematics professor at West Point, marred by the death of his wife and three children in seven months’ time. Greene began considering other occupations, studied engineering, and in 1836 resigned his commission in the army. His new career as a civil engineer would be long and fruitful. Those attributes also applied to George’s second marriage, which occurred at that time. The years passed in a succession of jobs from Maine to Virginia.

Greene was working on the Croton Reservoir in Central Park in New York City when the storm of Civil War broke over the land. His offer of service was answered in Albany with a commission as colonel of the 60th New York Volunteer Infantry. The 60th’s new commander was sixty-one years old.

Greene was at the front only briefly before he was promoted to brigadier general in April 1862. Then followed the service which earned an excellent record for his brigade. George Greene and his New Yorkers capped good performances at Cedar Mountain, Antietam, and Chancellorsville with their heroic defense of Culp’s Hill during the Battle of Gettysburg.

At about half-past seven on the evening of July 2, 1863, three Confederate brigades crossed Rock Creek and began to climb the eastern slope of Culp’s Hill. Above them, screened by the thick woods, waited Greene’s five New York regiments, comprising the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, 12th Corps. The New Yorkers were well entrenched behind log breastworks, constructed under Greene’s direction, but were spread thinly along the line and were heavily outnumbered. The rest of the 12th Corps had been detached to reinforce the left of the Union line. Greene’s 1,400 men were all that stood between the Confederates and the rear of the Union army. And they stood, beating back the Confederate attack in three hours of continuous fighting. General Greene later wrote, “Of the disastrous consequences to the Union army, had Lee succeeded in penetrating our lines and placing himself square across the Baltimore pike in rear of the center and right wing of the entire army, there can be no question. Fortunately it was averted by the steady and determined courage of the five New York regiments. . . .” Monuments to Greene’s regiments, and a larger-than-life statue of their commander, stand on Culp’s Hill today, erected by the State of New York to commemorate their heroic actions.

Gettysburg, the zenith of Greene’s career, was followed by some calamity. In the October 1863 night battle at Wauhatchie, near Chattanooga, Tennessee, a bullet ripped through Greene’s jaw and sidelined him from the war. (A month later, his son Charles had a leg shot off in battle. Another son, Samuel Dana Greene, who won renown as executive officer of the Monitor, eventually committed suicide.) The old general could not be kept down, however, and a month after his wounding he was on court martial duty. After enduring what was described as “a severe and altogether novel surgical operation” and a period of recuperation, Greene rejoined the army in time of General William Tecumseh Sherman’s final campaign in North Carolina, where, in a battle at Kinston, he had a horse shot from under him.

In 1866, General Greene resigned his commission and returned to his peacetime profession of engineering. He was 67 years old and worked for the next twenty years on major projects in Washington, Detroit, Troy, Yonkers, and elsewhere. Among Greene’s positions were chief engineer of public works in Washington, D.C., and head of the Croton Aqueduct Department, where his work had been interrupted by the war. At age 86, he examined the aqueduct by walking its thirty-mile length. He founded the American Society of Civil Engineers and served as its president for two years.

Greene moved to Morristown, New Jersey in 1883. His post-bellum interests included veterans’ affairs and genealogical work. He wrote a Greene genealogy and was president of the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society. He also closely followed the affairs of the Military Academy, and was the oldest living West Point graduate for several years. General Greene died in Morristown in 1899, aged 97. His remains were brought to Apponaug and buried there. A boulder from Culp’s Hill marks his grave site in the historic — but sadly neglected and routinely vandalized — Greene Cemetery, off Greenwich Avenue. A bronze plaque in the Rhode Island State House in Providence commemorates the significant military achievements of George Sears Greene.

Isaac Peace Rodman

Most of the life of Isaac Peace Rodman was a reflection of his middle name. Born in South Kingstown in 1822, he was still there when the war started. In the intervening years he attended school, joined his father in business, became a prominent merchant, and was elected to the town council and both houses of the Rhode Island legislature. His wife, Sally, was a sister of General Richard Arnold. The Rodmans had five children. Isaac was a devout churchman and taught Sunday school. As a Quaker, his allegiances to his religion and to the Union cause were in conflict. But when Fort Sumter was fired on, Rodman did not hesitate. He raised and became a captain of a company in the 2nd Rhode Island, and fought with them at Bull Run. Three months later, in October 1861, Rodman became colonel of the 4th Rhode Island. Early the following year the regiment participated in Burnside’s expedition to North Carolina. At the battles of Roanoke Island and New Bern, commander and regiment distinguished themselves. The charge of the 4th Rhode Island under the impetus of Rodman was decisive at New Bern, and earned his promotion to brigadier general a month later.

At the New Bern battle, on March 14, 1862, Rodman offered to assault the center of the enemy line, perceiving an opening where the railroad crossed the Confederate entrenchments. He had barely received permission when he led the 4th Rhode Island on an impetuous charge, breaking the Rebel line and capturing nine pieces of artillery. “Rodman’s soldierly movement was the culminating point of the day,” an officer later wrote, and the historian of the 9th Corps commented, “Colonel Rodman, with a fine soldierly instinct, perceived that the enemy’s line could be there successfully pierced, and his prompt and daring spirit suggested that, without losing time in waiting for orders, he should take advantage of the opportunity so fortunately offered.” Later in the North Carolina coastal campaign, Rodman was stricken with typhoid fever and returned to his South Kingstown home to recuperate.

When he rejoined the army, Rodman took over the 3rd Division of Burnside 9th Corps. His new command was minimally involved in the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, 1862. Three days later brought America’s bloodiest day, a massive, hideous battle in the Maryland countryside near and along the banks of Antietam Creek. Burnside, while making a small bridge famous by attacking it repeatedly, sent General Rodman and his division to cross at a ford down the creek. The march was made and the creek forded under a galling fire, but the attack was slowed and stopped by the counterattack of A. P. Hill’s Division of six brigades. Rodman was bringing up his old regiment, the 4th Rhode Island, when he was struck by a minie bullet in the chest. It penetrated his left lung and knocked him from his horse.

He was taken to a field hospital set up at the Rohrback house. When he was stripped, a bloodstained Bible was found inside his shirt. He remained lucid, and although he knew his wound was mortal and he suffered great pain from internal bleeding, he never complained and was calm, composed, and submissive. When the news reached South Kingstown, his wife, father, and family journeyed to Maryland. They were at his side when Isaac Rodman died, thirteen days after his wounding, on September 30, 1862. The Rodmans brought his remains home, and laid them to rest in the family cemetery in Peace Dale.

General Burnside, in an order to the corps, declared, “One of the first to leave his home at his country’s call, General Rodman in his constant and unwearied service, now ended by his untimely death, has left a bright record of earnest patriotism undimmed by one thought of self. Respected and esteemed in the various relations of his life, the army mourns his loss as a pure-hearted patriot and a brave, devoted soldiers, and his division will miss a gallant leader who was always foremost at the post of danger.”

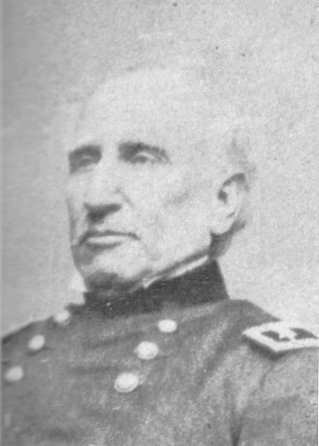

Thomas West Sherman

It was Thomas West Sherman’s lot to be totally eclipsed by a brilliant soldier with the same last name, and to suffer bitter disappointment during the Civil War. Born in Newport in 1813, Tom Sherman had military ambitions from his youth. It was said that he persuaded a fisherman to row him across Narragansett Bay, and then he walked to New York to be examined for entrance to West Point. He was successful in entering the academy and completed the course in 1836. He became an artillery officer and saw service in Indian conflicts and the Mexican War, when he won a brevet to major for gallantry at the Battle of Buena Vista. He was doing duty on the frontier when he married the daughter of Kansas territorial governor Wilson Shannon. He also served during the antebellum years in Minnesota, the Dakota Territory, and at Fort Moultrie in Charleston harbor.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, Sherman was called to Washington, appointed a brigadier general, and given a golden opportunity — command of the land forces in the amphibious expedition against Port Royal, on the coast of South Carolina. Port Royal fell, but Sherman’s performance displeased the government and he was relieved. After a brief tenure in command of a division in the advance on Cornith, Mississippi, he was again relieved and placed in command of the defenses of New Orleans. Early in 1863, Sherman was named to command to 2nd Division of General Nathaniel Banks’s 19th Corps. In the assault on Port Hudson, Louisiana, May 27, 1863, General Sherman was on horseback in the advance of his charging soldiers when he was shot in the right leg. The wound resulted in an amputation at the thigh, and his active service was over. About ten months later he returned to his New Orleans command and remained until after the war’s end.

In 1865 General Sherman was brevetted major general in both the regular and volunteer service. Resuming life in the regular army, he became colonel of the 3rd Artillery and with it garrisoned several posts on the Atlantic coast, including Key West. For a time he was stationed at Fort Adams, in his home town of Newport. In 1868, he was briefly in command of the Department of the East. In 1870 he was invalided out of the army with the rank of major general. General Sherman died nine years later in Newport (his wife Mary had died four days earlier). He is buried in Island Cemetery in Newport. (Also buried there are Union generals Isaac Stevens, who was killed at Chantilly, and Gouverneur K. Warren of Gettysburg fame.)

Frank Wheaton

Frank Wheaton was the youngest of the Rhode Islanders to become general, but he saw the most combat. Born in Providence in 1833, he was studying engineering when he left Brown University at age seventeen to take a position on a survey of the Mexican-American Boundary Commission. For five years he surveyed in the southwest and encountered hostile Comanches and Apaches. He was in Sonora, Mexico, when he received an appointment as lieutenant in the 1st United States Cavalry. Until the Civil War, Wheaton served throughout the West in Indian campaigns and on other duty. When the war broke out, the parents of Wheaton’s wife, Maria, sided with the Confederacy. His mother-in-law was a sister of Senator James Mason, soon to be famous as a result of the Mason and Slidell affair, when those two Confederate commissioners were seized from the British mail packet Trent by the United States navy. Wheaton’s father-in-law was Samuel Cooper, adjutant general of the army, who sided with Virginia and became the ranking general officer of the Confederacy. Maria Cooper Wheaton stood by her husband Frank.

On July 16, 1861, Wheaton was appointed lieutenant colonel of the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteers and five days later was promoted to the colonelcy at the Battle of Bull Run by Governor William Sprague, who was on the battlefield, following the death of Colonel John Slocum. Wheaton led his Rhode Islanders in the battles on the Peninsula and he was commended for his conduct at the Battle of Williamsburg. At Antietam his horse was hot dead under him, the first of five to share that fate during the war. Promoted in November 1862 to command a brigade in the 6th Corps, Wheaton fought with the Army of the Potomac at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. He led a division to the relief of Washington during the Confederate raid of 1864 and in General Philip Sheridan’s subsequent campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. For his services with Sheridan, Wheaton was brevetted major general in the regular and volunteer armies.

After Appomattox, he was mustered out of the volunteers in 1866, and became lieutenant colonel of the 39th Infantry. He saw extensive service in the West. He led the 1873 expedition against Captain Jack and his band of Modocs in the Lava Beds of northern California. After an army career of 48 years, 55 battles or skirmishes, and successive promotions to the rank of major general, Frank Wheaton died in Washington, D.C., in 1903. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, where a monument erected by the State of Rhode Island marks his grave.

The monument was dedicated on October 19, 1904, the fortieth anniversary of the Battle of Cedar Creek, in which action General Wheaton had distinguished himself. The monument committee, in its report to the Rhode Island General Assembly, declared, “In honoring the memory of General Wheaton our State has honored itself. General Wheaton was a Rhode Island man, with all the pride in his native State that every true son of Rhode Island should feel. His career in the service of our country was a noble one, and won the reward that comes to a brave and faithful soldier.”